An Agronomic Explanation of Timing, Volume, and Scale

Most irrigation failures do not happen because farmers lack data. They happen when a measurement is treated as a decision.

If you have ever heard, or said, one of these sentences, you have seen the problem in the field:

-

“The probe says we are fine, but the crop is stressed.”

-

“ETc says irrigate, but the sensor hardly moved.”

-

“We followed the recommendation and still got uneven yield.”

These situations occur because two fundamentally different concepts are often mixed into a single dashboard: crop demand, which reflects what the atmosphere is pulling from the canopy, and soil supply, which reflects what the root zone can actually deliver.

When growers manage irrigation using only one of these perspectives, the system may look precise on screen but behave inconsistently in the field.

ET, crop coefficients, and weather data are predictive by nature. They support irrigation planning by estimating future crop demand. Satellite imagery and soil sensors serve a different role: they describe the system’s actual state and response, with sensors reflecting soil conditions and remote sensing reflecting crop status. Confusion arises when planning tools are treated as measurements, or when measurements are treated as control signals.

In practice, the roles are clear:

-

Digital methods based on satellite imagery and weather data are best suited to determine timing and spatial variability.

-

Soil sensors are best suited for explaining what happened below ground.

-

Irrigation volume decisions fail when growers use a single sensor reading to represent an entire field or zone.

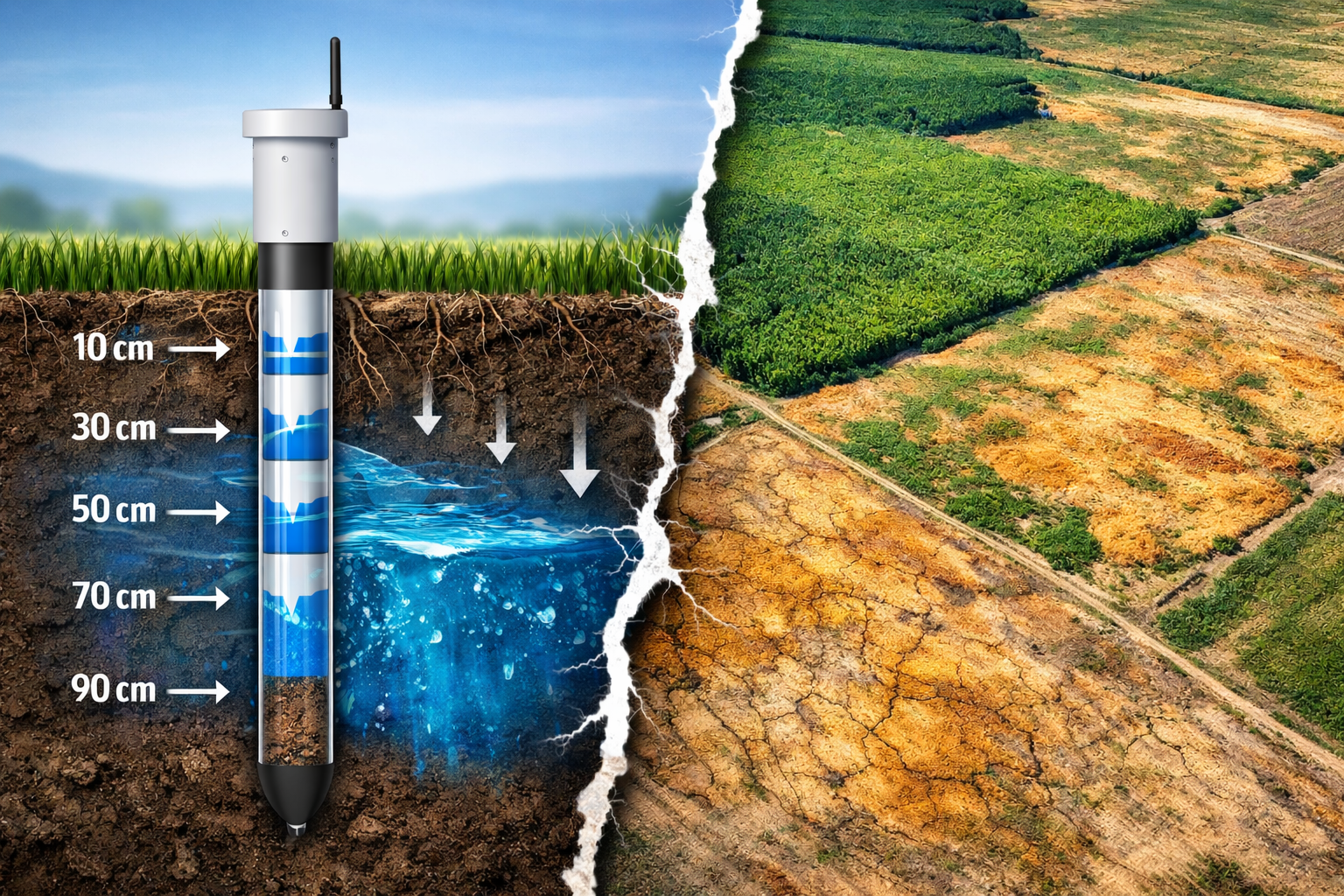

What Soil Moisture Sensors Actually Measure

Soil moisture sensors measure the physical status of water in the soil at a specific location. Depending on the technology, they report volumetric water content or matric potential at one depth or several depths along a vertical profile.

Even advanced multi-depth probes sample only a very small volume of soil at a single horizontal point. They describe local soil conditions with high precision, but they do not directly describe how the crop interacts with the soil at field scale.

Water uptake depends on root density, root activity, oxygen availability, soil structure, and mechanical resistance.

These factors determine whether roots can actually absorb water from the soil, and soil sensors do not measure them.

Practical implication: a “wet” reading can still mean limited uptake due to poor aeration, compaction, or weak rooting. A “dry” reading can still occur without visible stress if roots are active elsewhere or the soil profile is buffering demand.

Point Measurements Have A Scale Problem (Even In Small Fields)

The core limitation of soil sensors is not field size. It exists at any scale. A sensor measures only its immediate proximity, often a very small soil volume around the sensing element.

That matters because soil moisture can change substantially over very short distances, even within the same irrigation event. Slight differences in soil texture, structure, compaction, organic matter, root density, or installation conditions can lead to different wetting and drying patterns just centimeters apart.

Even small stones, cracks, or slight micro-topographic differences can alter local water movement and capillary continuity, causing soil moisture readings to diverge significantly over distances of just a few centimeters.

These micro-scale differences affect:

- Infiltration and redistribution after irrigation

- Drainage losses

- Root water uptake efficiency

- Local volumetric water content due to texture lenses, aggregate structure, cracks, macropores, worm channels, old wheel tracks, and micro-relief that shifts water flow

A simple way to think about it:

- The probe measures a point (and a very small point).

- You irrigate a surface (even a small block contains multiple micro-environments).

When those two scales are treated as equal, the recommendation becomes a guess with decimals. The sensor can be accurate at its spot while still being a risky control signal for irrigation volume.

Do Soil Sensors Show Water Uptake?

Soil sensors do not measure water uptake by roots. They measure changes in soil water status at a point.

What is often interpreted as uptake is inferred depletion, which can result from:

- Root water uptake

- Drainage below the sensor depth

- Lateral redistribution to other soil zones

- Evaporation from upper layers

- Capillary movement toward drier zones

The sensor cannot separate these processes. It only reports that water content at that location has changed.

Root water uptake is spatially uneven and temporally dynamic. A sensor placed in a zone with low root density may show little depletion even when the crop is transpiring heavily. Another sensor nearby may show rapid decline. Both readings can occur under the same crop demand.

Multi-depth sensors help identify vertical movement, but they still sample a narrow column of soil. Uptake occurring just centimeters away remains invisible.

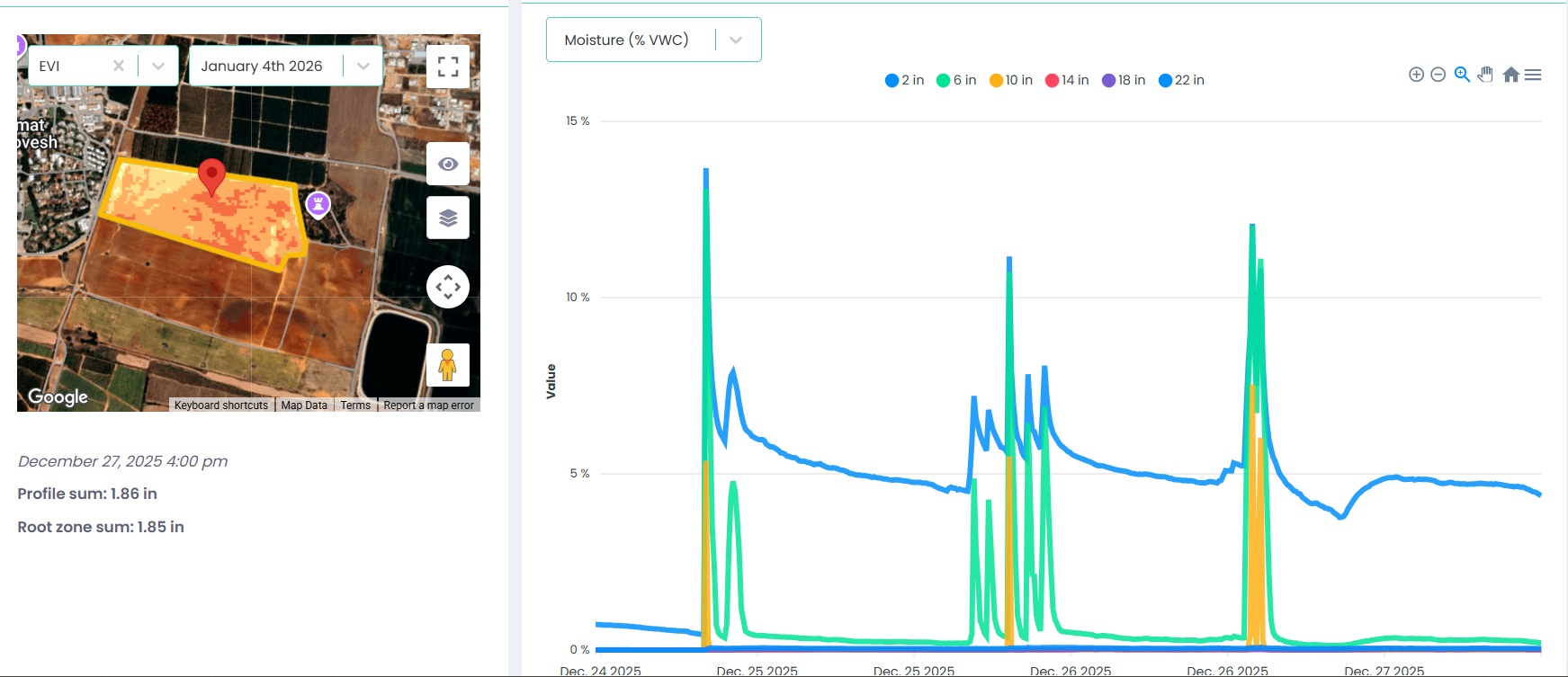

The probe captures detailed vertical moisture dynamics at one location, while the field map highlights spatial variability beyond that point. This image shows water penetrating deeper layers at a stage when canopy development is still limited, a pattern consistent with over-irrigation relative to crop uptake.

Volumetric Sensors And The Uncertainty Behind Field Capacity

Volumetric soil moisture readings have limited agronomic meaning unless they are interpreted relative to two reference points: field capacity and wilting point.

These define the range of plant-available water and are required to calculate depletion and irrigation volume.

In practice, these reference points are rarely measured directly. Field capacity varies with soil texture, structure, organic matter, compaction, and depth. Wilting point varies with soil properties and crop-specific root extraction capacity. Neither value is uniform across a field or even across a soil profile.

Instead, field capacity and wilting point are typically:

- Taken from generic texture-based tables

- Inferred from short-term sensor behavior after irrigation or rainfall

- Adjusted manually until the values appear reasonable

All of these approaches involve estimation. As a result, even when volumetric moisture is measured accurately, its interpretation rests on uncertain boundaries. Small errors in assumed field capacity or wilting point propagate into large errors when irrigation volumes are calculated.

What Digital Irrigation Scheduling Represents

Digital irrigation scheduling systems based on satellite imagery and weather data focus on crop demand rather than soil supply.

They estimate evapotranspiration, detect canopy stress, map spatial variability across fields, and integrate weather forecasts to anticipate future demand.

Their strengths include:

- Full-field spatial coverage

- Identification of variability between zones

- Forward-looking risk assessment

They align well with how crops experience water stress, which is driven primarily by atmospheric demand and canopy function.

Their limitations are structural. ET models assume water can be extracted when demanded. Satellite-based stress indicators reflect canopy response, which often appears after root-zone constraints have already limited uptake.

Digital methods indicate where and when the crop needs water. They do not confirm whether the soil can physically supply that water at the required rate.

Why Sensor Data And ET Estimates Rarely Agree

The frequent mismatch between soil sensor readings and ET-based demand estimates is often interpreted as error. In reality, it reflects two different processes being measured.

ET represents atmospheric demand averaged over space and time. Soil sensors represent local soil conditions shaped by structure, infiltration, redistribution, and root activity. The relationship between the two is neither linear nor stable during the season.

Expecting consistent agreement between these signals misunderstands their agronomic roles.

When Soil Sensors Add Real Value

Soil sensors are most effective as diagnostic tools. They are particularly useful for:

- Verifying how irrigation water moves through the soil profile

- Identifying drainage losses below the active root zone

- Detecting zones where water accumulates but roots struggle to function

- Explaining why expected crop responses to irrigation did not occur

In practice, there are very few systems where soil sensors can reliably support irrigation volumes on their own. Sensors may support irrigation volumes only in highly controlled environments with genuinely uniform soils, well-characterized root zones, and tightly managed hydraulic conditions.

What Works Agronomically In Practice

Reliable irrigation management combines crop demand estimation with soil behavior interpretation.

Environmental data and crop models are used to estimate when and where the crop is likely to require water, based on weather, canopy development, and spatial variability.

Soil sensors are then used to evaluate whether the soil-root system can realistically support those irrigation decisions. They help identify limiting factors such as poor infiltration, excessive drainage, oxygen stress, compaction, or shallow effective rooting that are invisible to crop demand models.

What this implies for digital platforms: irrigation decision support works best when the primary layer is built around crop demand and spatial variability, while soil sensors are integrated as optional validation tools rather than primary controllers. Environmental data, satellite imagery, and crop models provide the framework for timing and risk assessment. Soil measurements then help confirm whether irrigation events actually behave as expected in the effective root zone, or whether local constraints such as infiltration limits, drainage, or oxygen stress are dominating the response.

This architecture stays robust even when sensors are unavailable, and it remains flexible when they are. It avoids hard dependency on one device, supports multiple sensor technologies via APIs, and matches agronomic reality: soil behavior varies locally, while irrigation decisions must be made at zone or field scale.

A practical decision rule that works

- Use digital methods to answer: Where is risk building, when should I irrigate, and how much?

- Use sensors to answer: Did the last irrigation actually wet the effective root zone, or did it bypass it?

If you remember one line

Irrigation succeeds when demand is estimated at field scale and soil constraints are verified locally.

When irrigation strategies are built around that logic, data sources complement each other. When they are not, additional data only increases confusion.

If you want to see how we apply this logic in the field, you can explore our irrigation workflow in yieldsApp.

How To Actually Irrigate (A Practical Agronomic Flow)

Step 1 – Determine timing (before looking at sensors)

Timing answers one question only: when does the crop enter water-stress risk if nothing is done?

- Estimate crop water demand using ET, crop stage, and canopy development.

- Project demand over the coming days using weather forecast.

- Use spatial data to identify zones where risk is building faster.

The output of this step is a time window, not a trigger.

Sensors are not required here and often add noise when used for timing.

Step 2 – Decide irrigation volume (before looking at sensor depletion)

Volume answers a different question: how much water is needed to recharge the effective root zone to a functional state?

- Define the effective root depth based on crop stage and observed rooting behavior.

- Choose a target recharge, not full field capacity.

- Respect system constraints such as infiltration rate, application method, and operating limits.

Volume is chosen as a management range (light, moderate, deep),

not as a millimeter-level calculation.

Step 3 – Apply irrigation

The irrigation event is executed based on the timing and volume logic above.

Step 4 – Use soil sensors after irrigation to validate behavior

Sensors are used after the event to answer diagnostic questions:

- Did water reach the effective root zone?

- Did it stop too shallow or bypass roots?

- Was drainage excessive?

- Did oxygen stress or compaction limit uptake?

If sensor response does not match expectations, the correction is made to the next volume or application strategy, not to the timing logic.

Step 5 – Adjust rules, not signals

Over time, irrigation improves by refining volume ranges, root-depth assumptions, and application strategy based on observed soil behavior.

The demand-based timing framework remains stable.

Key principle:

Timing comes from crop demand and risk.

Volume comes from root-zone targets and system limits.

Sensors verify whether the soil behaved as expected.